4. Rethinking Uncertainty: A Half-Filled Glass and the Birth of “Need for Consideration”

Uncertainty isn't just about what we don't know — it's about how we think through what we find. Here's how a half-filled glass of water reshapes our understanding of information processing.

So, we know that uncertainty drives people to give more consideration to information. But just how does that uncertainty shape how deeply you think, or how confident you become in your opinions?

Previous studies have hinted at this — that uncertainty prompts users to engage in deliberation, helping them build confidence in their attitudes. But surprisingly few studies have focused on actually defining or measuring this deeper psychological function of uncertainty.

🥛 Half-Empty, Half-Full: The Dual Nature of Uncertainty

Let’s begin with a simple metaphor. Imagine a half-filled glass of water.

Do you see it as half-full? Or half-empty?

Your answer reflects more than just optimism or pessimism — it reflects how you interpret uncertainty.

And that’s exactly the problem communication scholars have wrestled with for decades: uncertainty isn’t inherently good or bad — it’s both. It depends on how people perceive it. This duality has given rise to multiple theories of uncertainty, each framing it in a different light.

For example:

Uncertainty Reduction Theory (URT) treats uncertainty as a negative state — a gap in knowledge that we’re motivated to eliminate (Berger & Calabrese, 1975).

In contrast, Uncertainty Management Theory (UMT) acknowledges that the other side of uncertainty can be functional, or even beneficial, depending on the situation (Brashers, 2001).

Behavioral economics chimes in, too. The concept of Knightian uncertainty describes those ambiguous situations where we can’t assign exact probabilities to outcomes. In those cases, people can swing between optimistic and pessimistic interpretations of the same unknown (Nishimura & Ozaki, 2017).

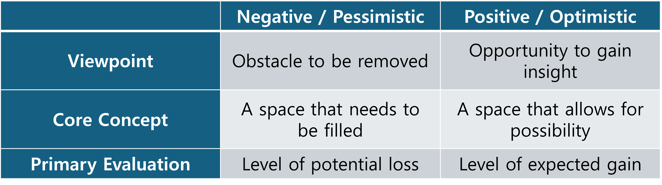

Pulling from these theories, we started to notice a pattern: people tend to process uncertainty through one of two main lenses:

This duality — seeing uncertainty as either risk or potential — plays a crucial role in how people approach information, especially when the issue is complex or divisive.

A New Typology: Mapping the Psychology of Uncertainty

Building on this dual framework, we developed a new way of categorizing uncertainty based on two axes: positivity and negativity. Think of it like a map, where each person’s mindset falls into one of four zones:

Indifferent (low-positivity, low-negativity):

Not much curiosity, low concern.

→ Low uncertaintyUnivalent-Optimistic (high-positivity, low-negativity):

Enthusiastic, confident, curious — but not worried.

→ Moderate uncertainty, driven by opportunityUnivalent-Pessimistic (low-positivity, high-negativity):

Concerned and anxious — but still engaged.

→ Moderate uncertainty, driven by fear or doubtAmbivalent (high-positivity, high-negativity):

Feeling both excited and uneasy. Motivated by the stakes, compelled to think hard.

→ High uncertainty

Among these, the ambivalent type represents the deepest level of cognitive engagement. People in this category are the ones most likely to pause, investigate, and truly consider the information they encounter.

From Need for Orientation to Need for Consideration

For decades, uncertainty was treated as a supporting character in agenda-setting theory — a lower-order concept of NFO. But as McCombs and Valenzuela (2020) noted, it hasn’t been frequently used in that role.

This new typology changes that.

By recognizing that uncertainty isn’t just about being unsure, but about how people emotionally and cognitively interpret ambiguity, we can use it to explain something deeper: the process of consideration.

And so, this study introduces a new concept: Need for Consideration (NFC) — the motivation not just to find information, but to seriously weigh its meaning.

Putting the Theory to the Test: Early Evidence from Political Polarization

The reconceptualized framework of uncertainty — what we’ve been calling Need for Consideration (NFC) — isn’t just a thought experiment. It has already begun to be tested in politically polarized contexts.

In a previous study (An et al., in press), this revised concept was applied to examine how people process politically sensitive information — specifically, how they responded to neutral news coverage of the 2019 Hong Kong protests. The results were telling.

Participants classified under the ‘ambivalent’ uncertainty type — those who experience both positive curiosity and cautious concern — showed no significant change in how important they perceived the issue to be right after reading neutral-toned articles. In other words, their sense of the issue’s significance was already established and remained consistent.

These same participants also maintained clear political stances (typically conservative in this case) and actively engaged in political behaviors from media consumption to discussion. Their inclination to use media selectively was defined not by reactivity, but by sustained, deliberate engagement.

In contrast, those categorized as ‘indifferent’ — characterized by a lack of strong prior opinions and minimal engagement with the issue — demonstrated a significant increase in perceived importance after reading the same articles. Their views were more easily influenced, suggesting that they may not have had strong prior stances or sufficient background knowledge to begin with.

These findings reinforce a key takeaway:

The new uncertainty types — especially NFC’s emphasis on ambivalence — offer a powerful lens for understanding how people evaluate information and form their stances towards divisive issues.

The Road Ahead: From Overlooked to Essential

The broader hope of this continuing research is to move uncertainty from the margins of agenda-setting theory to its conceptual center.

NFC offers a clearer way to model how people deliberate when the stakes are high and the information is complex. While this early application focused on political engagement, the same model could apply to other divisive and ambiguous issues, which have outcomes that are hard to predict, such as the application of AI (Artificial Intelligence) technologies.

Ultimately, this reconceptualization asks scholars to revisit a long-overlooked piece of the puzzle and ask:

What if uncertainty isn’t just a gap — but the key to how we think?

If other researchers begin applying these classifications in new domains, NFC could reshape how we understand orientation, deliberation, and decision-making in a world saturated with complex issues.

Seohyun (Gilly) An

Ph.D., Postdoc Researcher Communication & Media Research Center, Ewha Womans University

11-1 Daehyun-Dong, Seodaemun-Gu Seoul, Korea (03760)

© 2025. All rights reserved.